Surreal Life – Canadian pop surrealism and artist Stephen Gibb

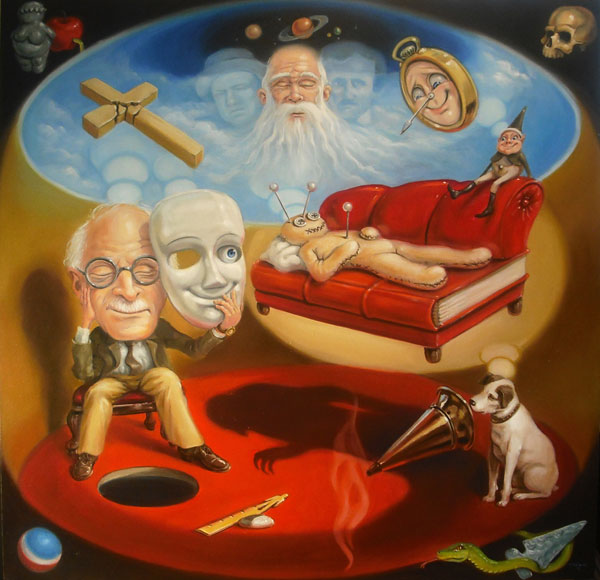

Anyone who creates something remotely surreal owes a debt to Freud, for delineating the concept of the “unconscious” mind, Andre Bretton, for formalizing the surreal process into a movement and Salvador Dali for rising to the top as their darling poster boy.

It was Dali who captured in oil paint the highly rendered, dream-like imagery of the wandering mind into a form that was both disturbing and intoxicating. Dali spawned thousands of imitators, emulators and admirers, and love him or hate him, his influence today is undeniable. He may have borrowed from the godfather of the surreal, Hieronymus Bosch, but as one time card-carrying contemporary of Surrealism, he was the painter exemplar.

I often hear comments from people that my work reminds them of Dali and I forgive them for being naïve but also understand that it’s just a convenient way to tag me. As a simple point of reference that helps them to share in some kind of “art” experience, I know I should be more tolerant. It used to make me insane but now I’ve become numb to it.

But really, why should I protest? People are making associations; connections, conclusions that may not be particularly original but at least they are exhibiting what essentially makes surrealism tick – the instinctive reflex for humans to seek meaning out of chaos. If this is how the “audience” makes sense of their perceptions, how does the artist encode their intentions?

There was a reason I mentioned Dali above because I am now going to use him and his ilk to demonstrate my thought process in explain how I came to paint the way I paint. Often asked, “Where do your ideas come from?” I can now attempt to expose some of that process in a few clumsy paragraphs.

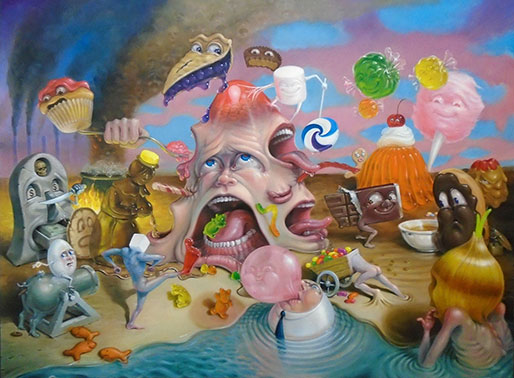

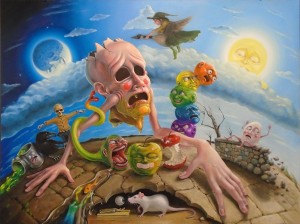

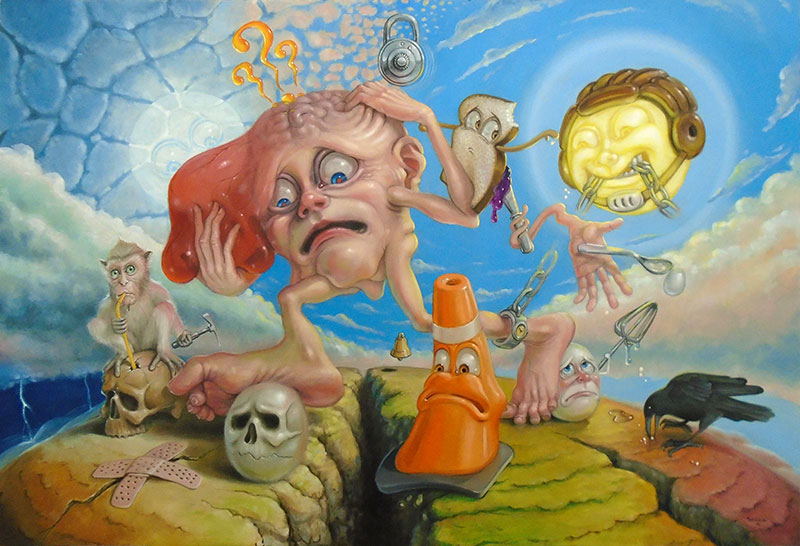

When I first encountered the work of Bosch, Breughel, Dali, De Chirico, Man Ray, Ernst, Magritte and others, I felt an immediate connection. No one had to explain or guide me through the subtleties of what I experienced. It was like a puzzle that had no conclusion, but was fun to unravel. That unsettling sense of familiar and unfamiliar blended into one form, touching the matchstick to the fuse in my powder keg mind is what drew me to the surreal. Something dreamlike, something innocent and perverse, something lurking in the shadows whispering inaudible prompts to draw you in, spin you blindfolded and shove you back into the world.

This is what art should be for me. Something that generates ideas, thoughts, and discussions and that just doesn’t pose as an answer. It should be embraced for the conceptual nudge it gives and not for some phantom truth that it strives for. It should be open-ended and mysterious, to open the floodgates of your reasoning and stir the colliding thoughts in a pot of egoless abandon. It should go with you once you leave it, and gnaw at your sleep. It should soak into your skin and enter your bloodstream. It should surprise you when it unexpectedly returns in your daily activity.

When confronted by surrealist art people are often hung up on meaning. “What does it mean?” is asked in haste and the question precedes the act of seeing. It also becomes the blind alley leading them away from self-discovery. To process without instruction is a liberty we should embrace. This is your chance to be creative with nothing more than a visual stimulus to get your cart moving. The elements of a surreal composition can set a tone and set you free to associate whatever idiosyncratic notions you may chance upon. There is no rulebook, map or schematic logic to follow. It’s up to you.

Return to main gallery

Return to main gallery

See more paintings from 2016

See more paintings from 2016

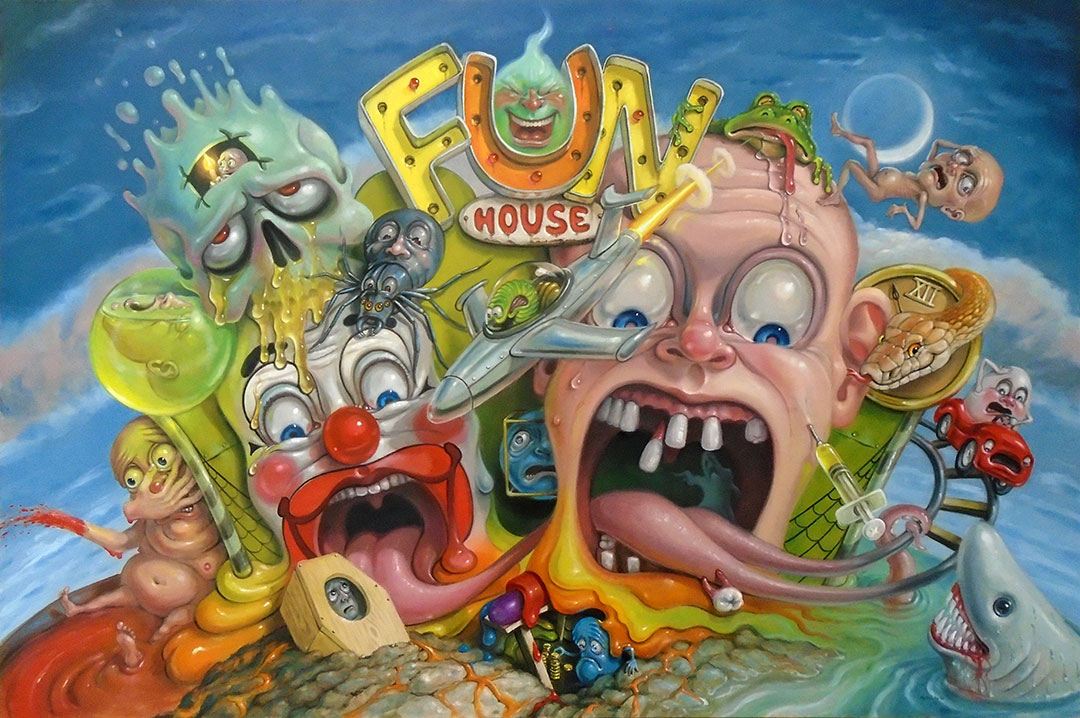

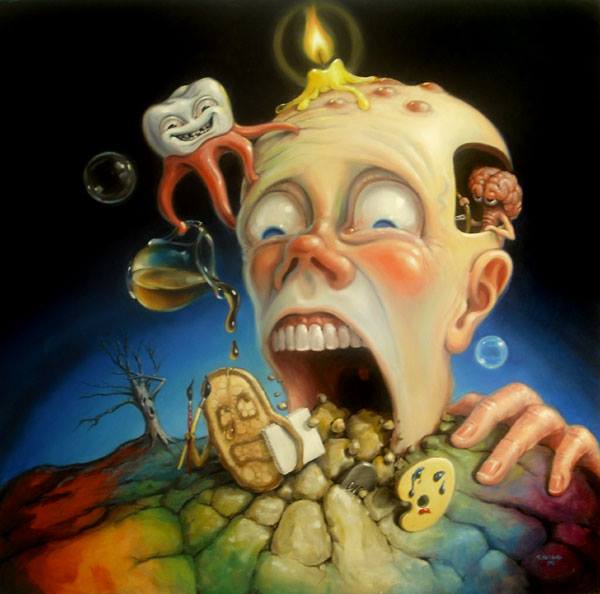

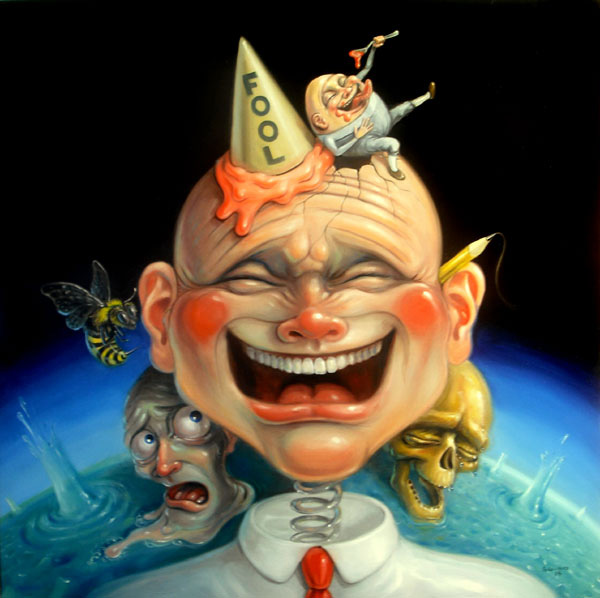

If I blow your mind, what will you do for me?

If I blow your mind, what will you do for me?

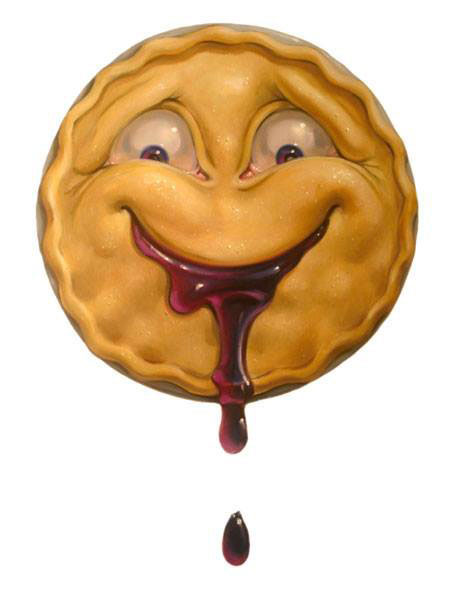

My obsession with Humpty Dumpty

Humpty Dumpty

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again…*

My obsession with Humpty Dumpty is both visual philosophical in nature. I am drawn to the famous egg visually, through his numerous portrayals in children’s books. His ovoid shape and cephalic body create a disconcerting strangeness that is hard to forget. Often styled with an equally strange grimace his impact on impressionable children is assured. One of the more famous portrayals is that by John Tenniel in Lewis Carrol’s Through the Looking-Glass (1872). Tenniel’s version of Humpty Dumpty with his wide slit mouth and creepy arched brows has stuck with me and penetrated many of my own characters in my paintings.

Aside from being physically creepy Humpty is also an egg. Frail, vulnerable and awkward he becomes a perfect symbol for the existential human. We are in constant state of alert when it comes to self-preservation and safety, something Humpty took too lightly. I often insert Humpty into my paintings as a symbolic representation of myself. Sometime he is just included as a frail human witness participating in my jumbled scenarios. He becomes a sympathetic entity that the viewer can hopefully identify with.

* The rhyme does not explicitly state that the subject is an egg, possibly because it may have been originally posed as a riddle. There are also various theories of an original “Humpty Dumpty”. One, advanced by Katherine Elwes Thomas in 1930 and adopted by Robert Ripley, posits that Humpty Dumpty is King Richard III of England, depicted as humpbacked in Tudor histories and particularly in Shakespeare’s play, and who was defeated, despite his armies, at Bosworth Field in 1485.

Professor David Daube suggested in The Oxford Magazine of 16 February 1956 that Humpty Dumpty was a “tortoise” siege engine, an armoured frame, used unsuccessfully to approach the walls of the Parliamentary held city of Gloucester in 1643 during the Siege of Gloucester in the English Civil War. This was on the basis of a contemporary account of the attack, but without evidence that the rhyme was connected. The theory was part of an anonymous series of articles on the origin of nursery rhymes and was widely acclaimed in academia, but it was derided by others as “ingenuity for ingenuity’s sake” and declared to be a spoof. The link was nevertheless popularised by a children’s opera All the King’s Men by Richard Rodney Bennett, first performed in 1969.

From 1996, the website of the Colchester tourist board attributed the origin of the rhyme to a cannon recorded as used from the church of St Mary-at-the-Wall by the Royalist defenders in the siege of 1648. In 1648, Colchester was a walled town with a castle and several churches and was protected by the city wall. The story given was that a large cannon, which the website claimed was colloquially called Humpty Dumpty, was strategically placed on the wall. A shot from a Parliamentary cannon succeeded in damaging the wall beneath Humpty Dumpty which caused the cannon to tumble to the ground. The Royalists (or Cavaliers, “all the King’s men”) attempted to raise Humpty Dumpty on to another part of the wall, but the cannon was so heavy that “All the King’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again”. Author Albert Jack claimed in his 2008 book Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes that there were two other verses supporting this claim. Elsewhere, he claimed to have found them in an “old dusty library, an even older book”, but did not state what the book was or where it was found. It has been pointed out that the two additional verses are not in the style of the seventeenth century or of the existing rhyme, and that they do not fit with the earliest printed versions of the rhyme, which do not mention horses and men. – source Wikipedia